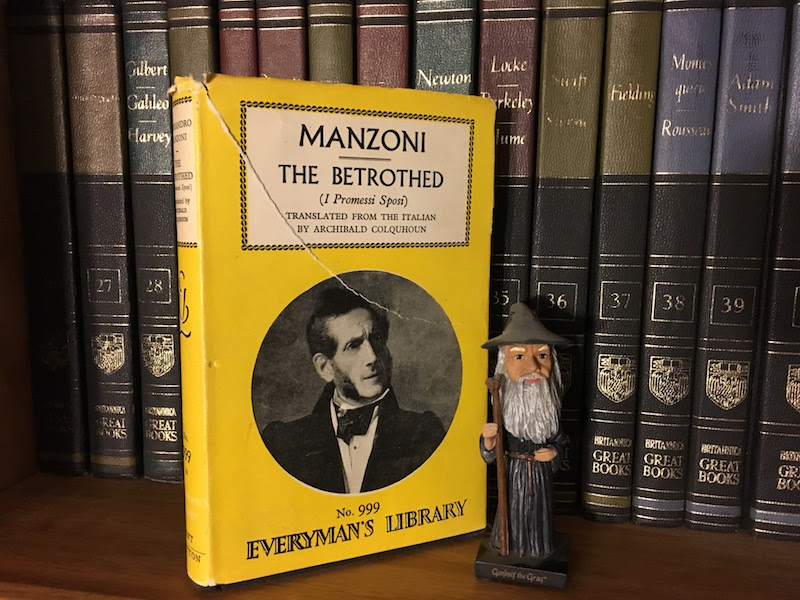

Reading The Betrothed by Alessandro Manzoni

I’ve been enjoying The Betrothed in a mellow sort of way, the way one enjoys a beer or glass of wine. Rather than gulping it down, I’ve been taking it in small sips. It’s that kind of book.

The Betrothed by Alessandro Manzoni is one of the books on my Catholic Classics Reading List. It appears in Fr. John Hardon’s Catholic Lifetime Reading Plan, in Harold Bloom’s The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages, and it is number 94 in Daniel Burt’s The Novel 100: A Ranking of the Greatest Novels of All Time. First published in 1828, The Betrothed is one of Italy’s most beloved novels, and as Daniel Burt writes,

Perhaps no other work of fiction, with the exception of Cervantes’s Don Quixote, has proven to be such a dominating native cultural icon as Manzoni’s novel, and no other work in Italy other than Dante’s Divine Comedy has done more to establish the literary language of Italian.

Manzoni writes with an economy not seen in contemporaries like Dickens or Hugo, though occasionally the plot has to wait while the narrator spends a chapter or two giving backstory to a new secondary character.

The story begins in a small village near Milan in 1628, when the marriage ceremony between two young peasants, Renzo and Lucia, is interrupted by the machinations of the evil nobleman Don Rodrigo. Don Rodrigo desires Lucia for himself, and the young couple have few allies powerful enough to help them against an influential man like Rodrigo. Things go from bad to worse after Rodrigo tries to have Lucia kidnapped.

The novel isn’t as melodramatic as I make it sound. The plot avoids the historical novel formula so common in other works of the time period. In The Catholic Lifetime Reading Plan Fr. Hardon comments,

Walter Scott gave Manzoni the inspiration to use the novel as the vehicle for deep religious convictions. But Manzoni differed from Scott in perspective. Instead of featuring the adventures, romances, intrigues and marvels so common in Scott, Manzoni concentrated on the interior, moral experiences of ordinary people. He believed that the deepest insights of human genius can best be expressed in the movements of a person’s conscience, rather than in colorful and adventurous exterior events.

Halfway through the book I have seen Manzoni’s interest in the interior lives of his characters. I can feel the plot building as I get further into the story and I’m anxious to find out the fate of the two young protagonists.