What Happened to the Magic? On Modern Fantasy Literature

Lory over at Emerald City Book Review has a wonderfully thought-provoking post about the her relationship with the fantasy genre. I began to leave a comment there but it ended up growing too long for a simple comment, so I offer my thoughts here. Here is how Lory began:

When I was growing up, I almost exclusively read fantasy. C.S. Lewis, George MacDonald, L. Frank Baum, Lewis Carroll, Ursula LeGuin, Madeleine L’Engle, E. Nesbit were the writers I read again and again, devouring every one of their books. In my teen years I idolized Robin McKinley, and became passionate about Diana Wynne Jones. Well into adulthood I pored over lists of best novels and tried out authors I didn’t much like, but could appreciate, like Michael Moorcock and Mervyn Peake…Now, even as I look forward to this event, I’m wondering about my current relationship to the genre. Fantasy is more popular than ever, but I seem to have drifted away from it, at least when it comes to new releases. Many of the books and series that others are raving about leave me cold; they seem too formulaic, too gimmicky, too dishonest and unconvincing, and sometimes just too silly. What happened to the magic?

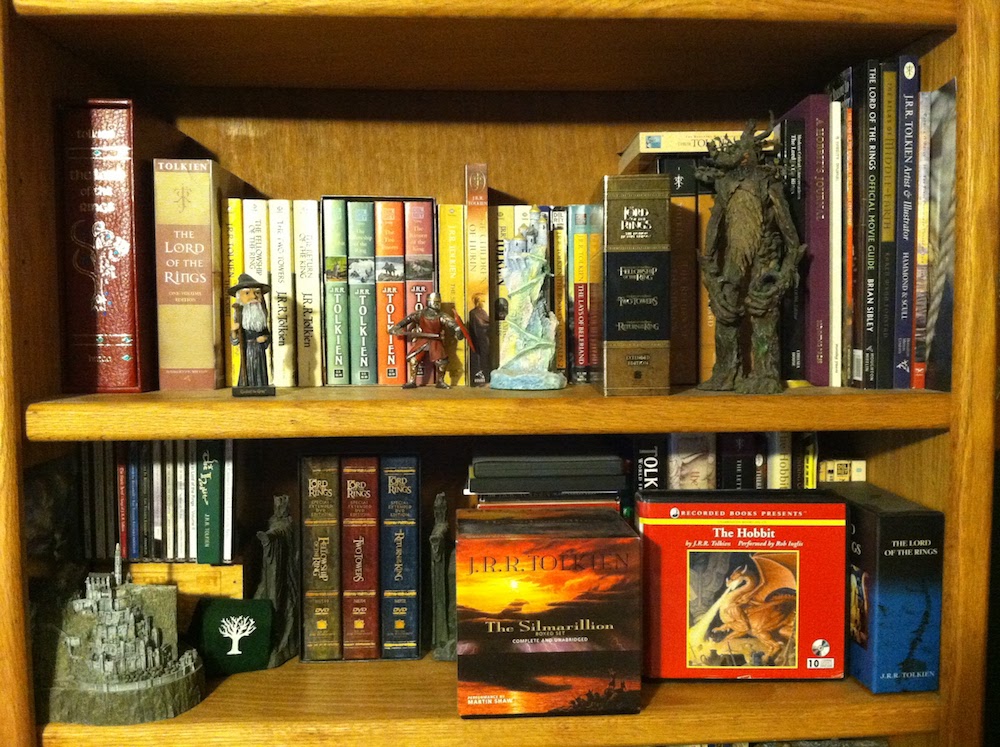

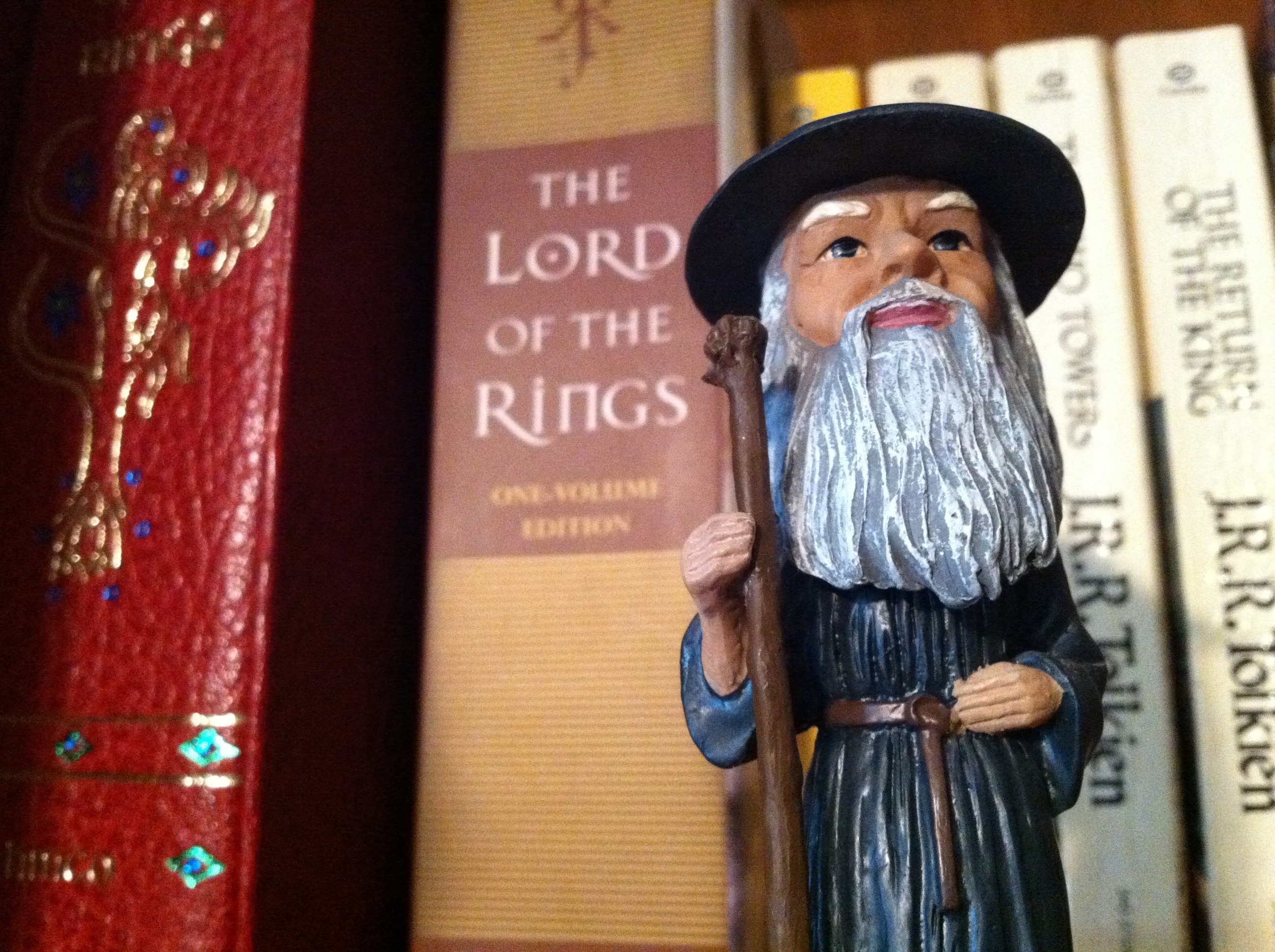

What happened to the magic, indeed? I feel exactly the same way–I was a huge fantasy fan growing up and into college, mostly of the epic or heroic fantasy authors: Tolkien, Lewis, Vance, Kay, even lighter fare by authors like Saberhagen, Brooks, Eddings, and Kurtz. But for decades I’ve been put off by most of the newer sci-fi/fantasy titles. Fantasy ceased to be interesting to me as a genre when it left behind its fairytale roots and instead became a remix of contemporary stories stuffed in a fantasy shell. Part of the change is the result of post-modern angst, part of it is the result of an industry trying to market to adolescents, no matter how old they may be.

But regardless of the reasons, this change is not unique to the fantasy genre. It’s across the board in imaginative fiction of all types and media, including comic books, movies, and TV shows, and is probably a reflection of modern culture’s lack of faith and trust in anyone in power, no matter how benevolent they are. Events like Watergate, Vietnam, religious and political scandals–you name it–can make fantasy from the 60s, 70s and 80s appear quaint and out dated. Today’s fantasy books are darker, grittier, and more violent, supposedly reflecting a more realistic view of humanity.

The lines between good and evil have become blurred as authors seeking to be original take villains from the past and rehabilitate them to present them as misunderstood. Disney is making an industry out of recasting old fairytale villains as victims. Part of that is a healthy realization that people are not all good or all evil–this is an important and necessary understanding about humanity, especially in our increasingly polarized culture.

But fairytales are a different type of storytelling, and I see the fantasy genre as continuing the important role of the fairytale as expressed by J.R.R. Tolkien in his landmark 1939 essay, “On Fairy Stories.”

First of all: if written with art, the prime value of fairy-stories will simply be that value which, as literature, they share with other literary forms. But fairy-stories offer also, in a peculiar degree or mode, these things: Fantasy, Recovery, Escape, Consolation, all things of which children have, as a rule, less need than older people. Most of them are nowadays very commonly considered to be bad for anybody.

Tolkien goes on to expand on each of those four elements:

Fantasy

Fantasy is a natural human activity. It certainly does not destroy or even insult Reason; and it does not either blunt the appetite for, nor obscure the perception of, scientific verity. On the contrary. The keener and clearer is the reason, the better fantasy will it make. If men were ever in a state in which they did not want to know or could not perceive truth (facts or evidence), then Fantasy would languish until they were cured. If they ever get into that state (it would not seem at all impossible), Fantasy will perish, and become Morbid Delusion.

Fantasy remains a human right: we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker…

Recovery

Recovery (which includes renewal and recovery of health) is a re-gaining – regaining of a clear view. I do not say “seeing things as they are” and involve myself with the philosophers, though I might venture to say “seeing things as we are (or were) meant to see them” – as things apart from ourselves. We need, in any case, to clean our windows; so that the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of triteness or familiarity – from possessiveness.

Escape

I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which “Escape” is now so often used: a tone for which the uses of the word outside literary criticism give no warrant at all. In what the misusers are fond of calling Real Life, Escape is evidently as a rule very practical, and may even be heroic. In real life it is difficult to blame it, unless it fails; in criticism it would seem to be the worse the better it succeeds. Evidently we are faced by a misuse of words, and also by a confusion of thought. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, be tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using Escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.

…

And lastly there is the oldest and deepest desire, the Great Escape: the Escape from Death. Fairystories provide many examples and modes of this – which might be called the genuine escapist, or (I would say) fugitive spirit. But so do other stories (notably those of scientific inspiration), and so do other studies. Fairy-stories are made by men not by fairies. The Human-stories of the elves are doubtless full of the Escape from Deathlessness.

Consolation

But the “consolation” of fairy tales has another aspect than the imaginative satisfaction of ancient desires. Far more important is the Consolation of the Happy Ending. Almost I would venture to assert that all complete fairy-stories must have it. At least I would say that Tragedy is the true form of Drama, its highest function; but the opposite is true of Fairy story. Since we do not appear to possess a word that expresses this opposite – I will call it Eucatastrophe. The eucatastrophic tale is the true form of fairy tale, and its highest function.

The consolation of fairy stories, the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous “turn” (for there is no true end to any fairy tale): this joy, which is one of the things which fairy stories can produce supremely well, is not essentially “escapist,” nor “fugitive.” In its fairy tale – or otherworld – setting, it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of joy, joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.

It is the mark of a good fairy story, of the higher or more complete kind, that however wild its events, however fantastic or terrible the adventures, it can give to child or man that hears it, when the “turn” comes, a catch of the breath, a beat and lifting of the heart, near to (or indeed accompanied by) tears, as keen as that given by any form of literary art, and having a peculiar quality.

Even modern fairy stories can produce this effect sometimes. It is not an easy thing to do; it depends on the whole story which is the setting of the, turn, and yet it reflects a glory backwards. A tale that in my measure succeeds in this point has not wholly failed, whatever flaws it may possess, and whatever mixture or confusion of purpose… Far more powerful and poignant is the effect in a serious tale of Faërie. In such stories when the sudden “turn” comes we get a piercing glimpse of joy, and heart’s desire, that for a moment passes outside the frame, rends indeed the wry web of story, and lets a gleam come through.

Where is the magic? To me it is in the stories that offer Fantasy, Recovery, Escape, and Consolation as described by Tolkien. I find it in in very few modern fantasy authors, but when it is there it is unmistakably wonderful: Patricia McKillip, Susanna Clarke, Naomi Novik. The problem is not that there are no fairytale writers anymore, but that there are so few of them–and so many imposters.

A good start in looking for fantasy stories that exemplify Tolkien’s four elements is to look to the winners of the Mythopoeic Fantasy Award. This award is given by the Mythopoeic Society to “the fantasy novel, multi-volume novel, or single-author story collection for adults published during the previous year that best exemplifies ‘the spirit of the Inklings.'” The Inklings, you may remember, was that inspired group of writers consisting of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and others. Here is how the society defines Mythopoeic Literature:

We define this as literature that creates a new and transformative mythology, or incorporates and transforms existing mythological material. Transformation is the key — mere static reference to mythological elements, invented or pre-existing, is not enough. The mythological elements must be of sufficient importance in the work to influence the spiritual, moral, and/or creative lives of the characters, and must reflect and support the author’s underlying themes. This type of work, at its best, should also inspire the reader to examine the importance of mythology in his or her own spiritual, moral, and creative development. Our members are a diverse lot, and their individual definitions of mythopoeic literature and its authors are equally diverse.

If more modern fantasy stories fit that description, I would read a lot more of it than I do now. For therein lies the magic.

Thanks for this super thoughtful post, Nick! I am definitely of the mythopoeic persuasion when it comes to fantasy, so the overrunning of that impulse by the “dark and gritty” elements could well be a factor in my disappointing experiences with many books. I see a silly and improbable current as well that bugs me — fantasy does not mean “hey I can write whatever I want and it doesn’t have to be convincing”; if anything it has to be MORE convincing than so-called realistic fiction, in my opinion.

Thankyou Lory and Nick for a couple of wonderful posts! Anyone who lists C.S. Lewis, George MacDonald, Ursula LeGuin, Madeleine L’Engle is someone after my own heart! I fear Fantasy has been a victim of its own success – everyone jumping on the bandwagon. Tolkien’s essay on fairy stories says it all really. It is getting hard to find the good stuff nowadays – or rather easy to find the not-so-good! Zelazny’s Amber series was pretty good, if you haven’t come cross it.

I went on a fascinating course yesterday at Sarum College, Winchester on “Doing Theology in Middle Earth”, but that’s another story!

Thanks for the comment, Robin! I’ve contemplated reading the Amber series many times but never got around to it. I’m glad to hear it’s in the same vein as the other fantasy I like. And someday I’d like to hear that story about “Doing Theology in Middle-earth!”