To Dance in our Woundedness: Homily for the Second Sunday of Easter – Year A

“These signs have been written that you may believe.”

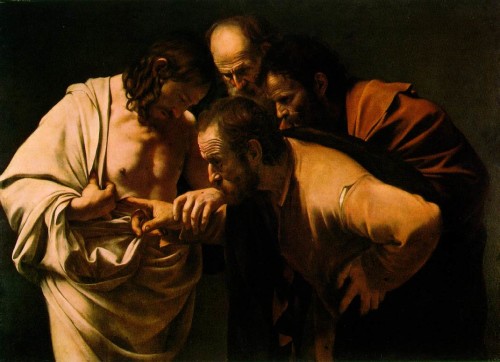

In today’s gospel, Thomas needs help in order to believe.

He needs a sign.

Who can blame him?

His friends were making a pretty far-fetched claim.

Jesus is risen from the dead?

Thomas had seen Jesus crucified.

“Prove it to me,” he says. “Show me the wounds.”

And Jesus does prove it to Thomas.

In his mercy, Jesus appears a week later.

Thomas sees the wounds.

He also sees the living Christ.

And he responds,

“My Lord and my God.”

Thomas needed to see both the wounds and the living Christ.

In our time, too, we look for signs.

We want to know that after the crucifixion comes the resurrection.

We’re all wounded in one way or another,

and we want to know that there is a life beyond our wounds.

All Thomas could think about were the wounds that Jesus had received.

Sometimes that’s all we can think about: our own wounds.

They’re so overwhelming

that we can’t see past them to new life.

If we want examples of the overwhelming power of woundedness

we only have to look at the lives of Angelo, Karl, and Amy.

Angelo was the son of a sharecropper in a small country village.

He lost his mother, a brother, and four sisters to cancer.

In fact, when his mother was close to death

his work duties prevented him from being there in her final hours.

Cancer was also to claim Angelo’s life–

stomach cancer.

It came in midst of a an monumental project he had started,

a project that he hoped would change the world.

He did not live to see that project completed.

Karl had his wounds to deal with too.

He once said,

“I was not at my mother’s death, I was not at my brother’s death,

I was not at my father’s death.

At twenty, I had already lost all the people I loved.”

Things got worse for Karl before they got better.

He had to hide from the Nazis,

He survived bullet wounds that perforated his colon and small intestines,

and in his old age he ended up struggling with Parkinson’s Disease.

And then there’s Amy.

Amy was only 19 years old when she was hospitalized with meningitis.

The meningitis affected her circulatory system, and within 24 hours,

the infection went into septic shock.

Doctors gave Amy less than a 2% chance of survival.

She lost both of her kidneys, her spleen, the hearing in her left ear,

and both of her legs had to be amputated below the knees.

Angelo, Karl, and Amy are signs of the woundedness of the world.

But we all walk through this life wounded.

Some of us are physically wounded,

others are emotionally or psychologically wounded,

and still others are spiritually wounded.

But in our woundedness

Jesus calls us to new life

so that we can be signs of faith to the world.

To be a Christian is to let our woundedness transform us.

That’s what Jesus shows Thomas, and that’s what he shows us.

“Put your finger here and see my hands,

and bring your hand and put it into my side,

and do not be unbelieving, but believe.”

The wounded Body of Christ is all around us, here in this church.

But the resurrected Christ is here, too.

Through his wounds, through our wounds,

we come to belief.

Easter is a call to be a sign of faith,

to show the world that our wounds do not get the final say.

This is what the disciples did.

They, too, were wounded.

They were hurt by the loss of their Lord.

As they gathered in the upper room

they felt the humiliation of having seen their savior

crucified by the Romans.

They were paralyzed by fear for their own lives.

When they huddled together in their woundedness

Jesus appeared in their midst

and showed them how to move from wounds to resurrection.

Out of the woundedness of Christ,

and out of their own woundedness,

the early Church came to new life.

And they drew people to Jesus.

How?

By devoting themselves to the teachings of the apostles,

to the communal life,

and to the breaking of the bread.

And that’s how we find new life in the face of our wounds.

Because we can arise out of our woundedness.

As a matter of fact, it is only through our wounds

that we can be resurrected.

If, in our woundedness,

we devote ourselves to the teachings of the apostles,

to the communal life,

and to the breaking of the bread,

then we are born into new life,

and we become signs of faith for the community.

People see us devoted, first, to the teachings of the apostles

when we acknowledge the truths of our faith,

even if they’re contrary to what we see in today’s culture.

When we hold fast to all that the apostles have handed on to us

in the midst of our pain and suffering

then the community understands the life that Christ offers.

We see this kind of devotion in Karl’s life.

Karl, in spite of an attempt on his life,

in spite of his struggles with Parkinson’s,

spent the majority of his life making the teachings of the apostles

clear and accessible to the Church,

and encouraging people to live those teachings to the full.

The second way to move from woundedness to life

is to be devoted to the communal life.

We are devoted to the communal life

when we help the poor,

taking care of those who need help

in the midst of our own woundedness.

When we share what we have,

even if it is only a little,

when we give of our time,

even when we are incredibly busy,

or lonely, or tired,

then the community sees the resurrected Christ

in our actions,

and we become signs of faith in our woundedness.

Amy’s life demonstrates how to live the communal life.

Amy,

in her struggles to get used to living without feet,

went on to found a non-profit organization for people with physical disabilities,

and she worked with another charity to bring shoes to children in developing countries.

In her woundedness

she found a way to help.

And finally, we are devoted to the breaking of the bread

when we gather here for Eucharist,

when we could just as easily be sleeping in

or going on a hike

or watching TV.

When we choose to spend our time in thanksgiving

with our parish community

we become like Christ showing his wounds to Thomas.

We come here broken, wounded,

and yet still grateful for our lives

and the graces we have received.

We see devotion to the breaking of the bread in Angelo’s life.

Angelo’s monumental project was to call the Second Vatican Council,

to gather all the bishops of the world

and renew the Church and her liturgy.

The world knows Angelo Roncalli as Pope John XXIII,

just as it knows Karl as Karol Wotyla, Pope John Paul II.

In spite of their wounds,

and even because of their wounds,

they became signs of faith to the world.

This weekend the world celebrates

as these two wounded men

are canonized as saints.

Millions of people gather in Rome

because they have seen the signs of faith

in the lives of St. John XXIII

and St. John Paul II.

But what about Amy?

Well, sometimes the signs of faith come from within the Church,

and sometimes they come from

someplace else.

Amy’s story doesn’t end with the loss of her kidneys, spleen or amputated feet.

It doesn’t even end with the non-profit she founded.

Amy became a snowboarder, winning back to back world cup gold medals.

But that’s not how I heard about her.

I first saw Amy while I was flipping through TV channels last week

looking for something to watch while I was grading papers for school.

I stumbled across the show “Dancing with the Stars,”

and there was Amy Purdy in a beautiful white dress,

dancing on her artificial feet.

She and her dance partner were leaping and twirling around the stage

to the song “Shout” by the Isley Brothers,

dancing a jive,

which, according to the judges, is the most difficult dance.

There she was with artificial feet strapped to the bottoms of her legs,

kicking and swinging and leaping with joy

while the Isley brothers sang,

“You know you make me want to shout.”

It made me want to shout

when I saw that woman dancing on prosthetic feet.

It was amazing to see a young woman with that kind of disability

performing with such life and joy and exhilaration.

Now, I don’t know Amy’s religious background,

but that’s the kind of joy and life and exhilaration

that can inspire people to come to Christ,

that can strengthen the faith of those of us who already know Christ.

Amy dances in her woundedness.

And isn’t that the very definition of resurrection?

To dance in our woundedness?

When we see people who are wounded,

dancing with life, dancing with exhilaration and joy

there’s something compelling in that,

something attractive and amazingly hopeful.

What a great image for us on this Divine Mercy Sunday.

In our woundedness we are to dance, we are to shout with joy

because the Lord is risen.

And it is through his wounds

That he has healed us.

“These signs have been written that you may believe.”

May we, like Angelo, Karl, and Amy,

use our wounds to be signs of faith

and bring Easter joy to the world.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS