The Isenheim Crucifixion – Homily for the Fifth Sunday of Lent

Do you remember the first picture of Jesus you ever saw?

Do you remember the first picture of Jesus you ever saw?

Was it a picture in a children’s Bible?

A coloring book page from Sunday school?

The actor Robert Powell in Jesus of Nazareth?

There are many famous images of Jesus,

and some of them hang on the walls of our homes.

There’s the famous Warner Sallman painting of the Head of Christ,

which has sold over 500 million copies.

There’s the familiar Sacred Heart of Jesus,

and the Divine Mercy image.

Another popular painting of Jesus

is the one where he stands outside the door knocking.

We could run through an entire catalog of famous paintings of Jesus:

in the manger at his birth, sitting on a bench surrounded by children,

carrying a lamb on his shoulders.

If the Greeks in today’s gospel had come to us and said,

“We would like to see Jesus,”

we have many paintings we could show them.

And yet, none of them would be the real Jesus.

All of them would be artistic interpretations of who he is.

They each reveal an important aspect of Jesus,

but none of them is complete.

We all carry around inside of us an incomplete picture of Jesus.

We carry these images in our minds

and they form our view of who Christ is.

It’s like seeing a movie before reading the book.

No matter how hard we try,

Frodo Baggins will always look like Elijah Wood;

Atticus Finch will always look like Gregory Peck;

The Godfather will always be Marlon Brando.

Who does Jesus look like to us?

The Greeks had heard all kinds of things about Jesus of Nazareth.

I wonder how they pictured him.

I wonder who they expected to see when they asked to see him.

Jesus the preacher? Jesus who turns water into wine?

Jesus who walks on water?

And what about us?

Who did we expect to see when we came to Mass today?

Like the Greeks, each of us has come here to see Jesus.

Each of us has an image of Jesus in our mind when we pray,

when we come to communion.

Who is the Jesus we have come to worship?

Whoever it is the Greeks wanted to see,

Jesus surprises them.

And maybe he surprises us.

He says that he is troubled.

He, who is usually so confident and divine in John’s gospel,

is disturbed that his hour has come.

He tells the Greeks and us

that unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies,

it remains just a grain of wheat;

in other words, he has come to die,

he has come to be the grain of wheat

that will become food for the world.

He is the one who has come to serve and be obedient

and who asks us to do the same.

Both the gospel and the letter to the Hebrews show us a Jesus

who learned obedience through suffering,

who offered prayers and supplications with loud cries and tears.

That’s not an image we see in paintings very often—

a Jesus sobbing in prayer for his people.

But that’s what we hear today: loud cries and tears;

a grain of wheat about to fall to the earth and die.

It’s a difficult Jesus to look at,

because that is who we are called to imitate.

We’re preparing for the holiest times of the year.

Today’s liturgy challenges us to seek the Christ who really is,

to get beyond images of our youth and get to know the real Christ,

not Christ as we want him to be.

In these remaining two weeks of Lent,

we’re asked to take some time to ourselves and ask

is there an aspect of Christ we have been avoiding?

Is there a part of Christ’s life and mission that we would rather not see?

There’s another famous painting of Jesus,

one that you probably won’t find in anyone’s house.

It’s disturbing, ugly, and very hard to look at.

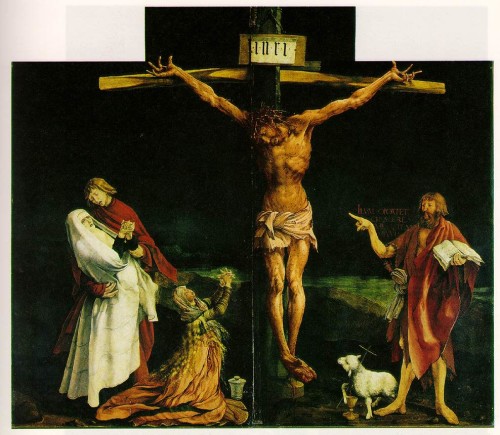

It’s called the Isenheim Altarpiece,

and it was painted by Matthias Grunewald around 500 years ago.

It’s made up of four panels, but the main scene is the crucifixion,

and it would be hard to find a more gruesome portrayal of Christ’s death.

In this crucifixion scene,

Grunewald paints Jesus with his hands gnarled and twisted,

facing up as if clawing to pull the spike out of the wood;

and his feet are all twisted together in an almost impossible position.

The body of Jesus is full of wood splinters and thorns.

But maybe the worst thing about the image is the color of Jesus’ flesh.

It’s a sickly green color, covered with spots, like it’s rotting.

It really is a hard painting to look at.

I’m not doing it justice at all, trying to describe it you.

It isn’t a painting that you just look at;

it’s a painting that you experience.

That’s the Jesus that is speaking to us today,

the Jesus of the Isenheim crucifixion.

The suffering servant who prays for us with loud cries and tears.

When we imagine Jesus, when we think of Jesus,

are we imagining who we want Jesus to be,

or are we willing to discover who Jesus really is?

It’s essential for us to really know Jesus

so that we can be his disciples.

“Whoever serves me must follow me,” Jesus says,

“and where I am, there also will my servant be.”

We are called to be that grain of wheat that falls to the ground and dies.

And when we look at a painting like the Grunewald Crucifixion,

when we see that disturbing scene of Jesus on the cross,

we get a better understanding of what it takes to be a follower of Jesus.

Maybe that frightens us.

Maybe we’d rather just look at the Jesus who knocks at the door,

who carries the lamb on his shoulders,

the Jesus of our childhood images.

But we don’t need to be afraid of what we’ll find

when we approach the real Jesus,

even if what we see is the Isenheim Altarpiece.

Because with Jesus, there’s always more than what meets the eye.

With Jesus there’s always hope in the midst of horrible suffering.

You see, what’s even more unusual about the Isenheim Altarpiece

is that it wasn’t painted to hang in a museum.

It was painted for the front of the altar in a monastery church,

the Monastery of St. Anthony in Isenheim, Germany.

That’s one of the things that makes this painting so famous.

It was used in a church.

Can you imagine coming to Mass here

and seeing this disturbing crucifixion scene in front of us

week after week?

Why would Grunewald paint such a horrific picture for a church?

It seems sadistic, perhaps.

But with Christ, suffering never has the last word.

Historians tell us that the monks of the Monastery of St. Anthony

specialized in hospital work,

especially for patients suffering from ergotism,

or what came to be known as “St. Anthony’s Fire.”

Ergotism was a horrible condition that occurred

when people ate grains or cereals that contained a certain fungus,

and it was almost like a plague during the Middle Ages.

It caused the skin to rot and shed,

and patients often had to have their limbs amputated.

People came to the Monastery of St. Anthony to be treated for ergotism,

and while they were there, they would go to Mass.

Grunewald painted his crucifixion scene for them.

The crucified Jesus of the Isenheim Altarpiece

has the symptoms of ergotism.

When the patients of the monastery came to Mass

they saw a God who suffered with them.

Where we see horror, they saw hope.

They saw a God who loves them.

And if God can take on that kind of suffering

and transform it into resurrection,

then our suffering can be transformed into resurrection.

That is the hope of Easter.

The challenge of today’s liturgy in these closing days of Lent

is to move beyond the images of Jesus

we’ve carried with us since childhood

and see the real Jesus;

to meet the Jesus we have been avoiding,

the Jesus we haven’t been seeing,

even if the sight is disturbing,

so that we, too can see in him the hope of Easter.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS